Wingin’ it in China

In the news at home, I read about Chinese politics, power, and pollution… but very little about the people that make up their country.

This trip was special not only because I met the individuals who were a part of my adoption story, but also because it humanized an entire country for me.

It created context for this place that could’ve… would’ve… maybe even should’ve… been my home. It instilled pride and understanding for my country of origin.

Table of Contents

1. How did you travel?

We read a lot of books.

We walked as if public transportation did not even exist.

We referenced local maps, matched the symbols, and meandered for hours.

2. How did you process the Nanjing Massacre of 1937?

The Rape of Nanjing eliminated 300,000 people within weeks.

300,000? Honestly, I couldn’t really comprehend that number. Like many statistics, I usually fail to understand the size and injustice of this event.

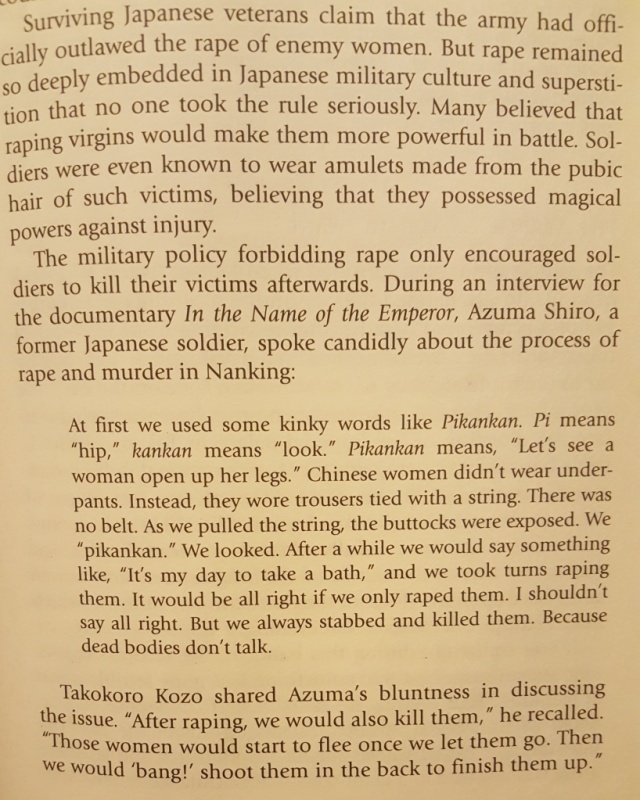

Reading Iris Chang’s “The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II” personalized the story of each individual victim. After processing the individual testimonies of horrific counts of murder, rape, and pillaging, it made me think about who would be affected if this were to happen today.

I thought about how the 300,000 victims included civilian children:

young people:

very old people:

and everyone in between:

When we visited the Nanjing Massacre museum, there was a wall of remembrance with the names of the victims engraved from floor to ceiling. We found about 7 names with my last name, Au 歐.

My family is from Southern China, so we didn’t expect to find too many in Nanjing which is located in Northern China… but we did.

We also found two entire columns, floor to ceiling, ceiling to floor, with the last name, Gao 高, meaning they were from Gaoyou 高邮, the city of my orphanage.

Potential aunts, uncles, long-lost relatives? I’ll never know.

3. How was your visit to your orphanage, Gaoyou Children’s Welfare Institution (CWI)?

So my aim isn’t great, but I am trying to point to the 21 year old girl in red, located in the upper-lefthand corner. Her name is Hua, which means flower in Chinese. She held me when I was a baby, and two decades later, we serendipitously met again!

Just like me, Hua was also dropped off at this orphanage at a young age.

However, unlike me, she was never adopted perhaps because of a very minor deformity in a few of her fingers.

In another circumstance, maybe she would’ve gotten surgery. Maybe she would’ve had been a deemed a “healthy baby” and had the chance to be adopted.

Looking back, I’m not sure a smile best encapsulates this moment. In reality, I felt a lot more contemplative and a bit uncomfortable thinking about how Hua and I were both orphans, yet because of our birth lottery, our outcomes were vastly different.

Today, Hua is a happy mother and wife. She proudly works at Gaoyou CWI as a loving caretaker. It was surreal to be able to spend time with her and silently share this reunion together.

You can read more about Gaoyou CWI here: http://www.aboutgaoyou.com/children/Gaoyou_CWI.aspx

4. Why did you choose this spot to take a picture?

We were here 21 years ago.

Except 21 years ago, I was in a stroller and my aunt had to carry me up all of the steps to the very top of Dr. Sun Yat Sen’s mausoleum. The grandeur and physical size of this mausoleum compliments the sentiment of the founding father of China very well.

5. Did you find answers?

We were able to confirm my birthplace. Maybe.

I was a result of China’s One Child Policy. Probably.

I have no clue who my birthparents are. And it will probably stay that way.

I know the exact date of my birthday. And in my mind, I feel much more comfortable celebrating the accomplishment of my mom successfully giving birth to a healthy baby girl than celebrating the day of my birth.

I traveled to China with very few expectations, and left with a treasure of profound memories and insights.

Thank you to my spunky mother and loving family for making my life so whole.

“I’m glad to see more baby girls” – my Mom.

January 1, 2016 marked the end of China’s one-child population planning policy, which restricted the majority of Chinese families to only one child since 1979.